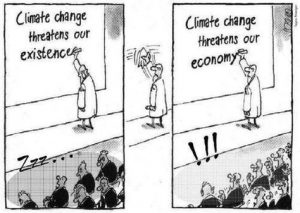

The non-governmental organizations and institutions dedicated to climate mitigation and adaptation have long been the backbone of efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions, develop sustainable technologies, and build resilient communities. However, the chilling effect of Donald Trump’s climate policies has cast a shadow over this critical work, obstructing progress at a time when urgent action is needed more than ever.

The non-governmental organizations and institutions dedicated to climate mitigation and adaptation have long been the backbone of efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions, develop sustainable technologies, and build resilient communities. However, the chilling effect of Donald Trump’s climate policies has cast a shadow over this critical work, obstructing progress at a time when urgent action is needed more than ever.

Trump’s systematic dismantling of climate policies—ranging from withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Agreement to rolling back emissions standards and cutting climate research funding—has created a hostile environment for those working in climate science, renewable energy, and environmental advocacy. With government leadership retreating, NGOs and private organizations face increased challenges in securing funding, influencing policy, and mobilizing public support for meaningful climate action.

Yet reducing global greenhouse gas emissions remains urgent. By reversing its climate policies, the U.S. is not only losing valuable time but actively accelerating the depletion of its remaining carbon budget. As climate models have long predicted, predictable climate-related disasters—wildfires, hurricanes, droughts, and sea-level rise—are arriving sooner and with greater intensity.

Continue reading “The Chilling Effect of Trump’s Climate Actions on the Climate Community”